Art and Symbols of the Occult Greenwich Editions London 1993

| Austin Osman Spare | |

|---|---|

Spare in 1904 | |

| Built-in | (1886-12-thirty)thirty December 1886 Snow Hill, almost Smithfield Market London, England |

| Died | 15 May 1956(1956-05-15) (anile 69) London, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Pedagogy | Imperial College of Art |

| Known for | Draughtsman, painter and occultist |

| Movement | Symbolism, Proto-Surrealism |

| Patron(south) | Pickford Waller, Desmond Coke, Ralph Strauss, Lord Howard de Walden, Charles Ricketts, Marc-André Raffalovich, John Greyness, Aleister Crowley. |

Austin Osman Spare (xxx December 1886 – fifteen May 1956) was an English language artist and occultist[1] [ii] who worked equally both a draughtsman and a painter. Influenced by symbolism and art nouveau his art was known for its clear use of line,[3] and its depiction of monstrous and sexual imagery.[4] In an occult capacity, he developed idiosyncratic magical techniques including automatic writing, automated drawing and sigilization based on his theories of the human relationship betwixt the conscious and unconscious self.

Born into a working-form family in Snow Loma in London, Spare grew upwards in Smithfield and so Kennington, taking an early involvement in fine art. Gaining a scholarship to study at the Royal Higher of Art in South Kensington, he trained every bit a draughtsman, while also taking a personal interest in Theosophy and Occultism, becoming briefly involved with Aleister Crowley and his A∴A∴. Developing his own personal occult philosophy, he wrote a series of occult grimoires, namely Globe Inferno (1905), The Book of Pleasure (1913) and The Focus of Life (1921). Alongside a cord of personal exhibitions, he as well achieved much press attention for being the youngest entrant at the 1904 Purple Academy summertime exhibition.

After publishing two brusque-lived fine art magazines, Form and The Gold Hind, during the First World War he was conscripted into the armed forces and worked as an official state of war artist. Moving to various working class areas of Due south London over the following decades, Spare lived in poverty, but continued exhibiting his work to varying degrees of success. With the arrival of surrealism onto the London fine art scene during the 1930s, critics and the press once more than took an involvement in his work, seeing it as an early on precursor to surrealist imagery. Losing his domicile during the Blitz, he roughshod into relative obscurity following the 2nd World War, although he continued exhibiting till his death in 1956.

Spare's spiritualist legacy was largely maintained by his friend, the Thelemite writer Kenneth Grant in the latter office of the 20th century, and his beliefs regarding sigils provided a primal influence on the anarchy magic motion and Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth. Spare'southward art in one case more than began to receive attention in the 1970s, due to a renewed interest in art nouveau in Britain, with several retrospective exhibitions being held in London.

Biography [edit]

Childhood: 1886–1900 [edit]

Austin's father, Philip Newton Spare, was built-in in Yorkshire in 1857, and moved to London, where he gained employment with the City of London Constabulary in 1878, being stationed at Snow Hill Constabulary Station. Austin's female parent, Eliza Osman, was built-in in Devon, the girl of a Royal Marine, and married Philip Newton Spare at St Helpmate's Church in Armada Street in December 1879. The Spare's first child to survive was John Newton Spare, born in 1882, with William Herbert Spare following in 1883 and then Susan Ann Spare in 1885.[five]

The couple's 4th surviving kid, Austin Osman Spare was born shortly after four o'clock on the forenoon of 30 December 1886.[5] Spare attended St. Agnes School, attached to a prominent Loftier Anglican church, and as a kid he was brought up inside the Anglican denomination of Christianity.[half-dozen] Taking an interest in cartoon, from most the historic period of 12, he began taking evening classes at Lambeth School of Art under the tutorship of Philip Connard.[7]

Artistic grooming: 1900–1905 [edit]

In 1900, Spare began working as a designer at Powell's glass-working business in Whitefriars Street, which had links to the Arts and Crafts movement and William Morris. In the evenings he attended the Lambeth Schoolhouse of Art.[eight] Two visitors to Powell's, Sir William Blake Richmond and FH Richmond RBA, came across some of Spare's drawings, and impressed, they recommended him for a scholarship to the Imperial College of Art (RCA) in South Kensington.[9] He accomplished further attention when his drawings were exhibited in the British Fine art Section of the St. Louis Exposition and the Paris International Exhibition, and in 1903 he won a silver medal at the National Contest of Schools of Art, where the judges, who included Walter Crane and Byam Shaw, praised his "remarkable sense of colour and great vigour of formulation."[10]

Shortly, he began studying at the RCA, but was dissatisfied with the education he received there, becoming a truant and being disciplined by his tutors every bit a issue.[11] Influenced by the work of Charles Ricketts, Edmund Sullivan, George Frederic Watts and Aubrey Beardsley, his artistic style focused on clear lines, which was in stark contrast to the Higher's accent on shading.[12] All the same living in his parents' home, he began dressing in unconventional and flamboyant garb, and became popular with other students at the higher, with a especially strong friendship developing between Spare and Sylvia Pankhurst, a prominent Suffragette and leftist apostle.[13]

After condign a practising occultist, he wrote and illustrated his offset grimoire, World Inferno (1905), in which he took as his premise Blavatsky's idea that Earth already was Hell. The work exhibited a variety of influences, including Theosophy, the Bible, Omar Khayyám, Dante'due south Inferno and his ain mystical ideas regarding Zos and Kia.

In May 1904, Spare held his first public art exhibition in the lobby of the Newington Public Library in Walworth Road. Hither, his paintings illustrated many of the themes that would go on to inspire him throughout his life, including his mystical views about Zos and Kia.[xiv] His father and so surreptitiously submitted two of Spare's drawings to the Royal University, one of which, a design for a bookplate, was accepted for exhibition at that yr's prestigious summertime exhibition. Journalists from the British press took a particular interest in his piece of work, highlighting the fact that, at seventeen years of age, he was the youngest creative person in the exhibition, with some erroneously claiming that he was the youngest artist to ever exhibit at the evidence.[fifteen] According to the media, G. F. Watts allegedly stated that "Young Spare has already done enough to justify his fame", while Augustus John was quoted as remarking that his draughtsmanship was "unsurpassed" and John Vocalist Sargent apparently thought that Spare was a "genius" who was the greatest draughtsman in England.[15] Gaining a pregnant level of press attention, journalists arrived at the Spare family household in Kennington to interview him, leading to a cord of manufactures in which he was praised equally an artistic prodigy. 1 alleged that he aspired to eventually become the President of the Majestic University itself, something he would quickly deny.[16] In 1905, in the midst of this media interest, he left the RCA without having received any qualifications.[17]

Early on career: 1906–1910 [edit]

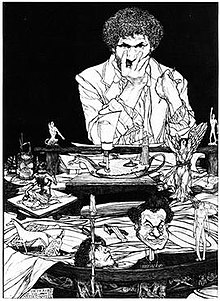

Having left higher didactics, Spare became employed as a bookplate designer and illustrator, with his first book commission beingness for Ethel Rolt Wheeler's Behind the Veil, published by the company David Nutt in 1906.[xviii] In ensuing years he would as well illustrate such texts as Charles Grindrod's The Shadow of the Raggedstone (1909) and Justice Darling'southward On the Oxford Excursion and other Verses (1909).[19] In 1905, he once more exhibited at the Royal University's summer exhibition, having submitted a drawing known as The Resurrection of Zoroaster, featuring beaked serpents swirling around the effigy of the ancient Western farsi philosopher who founded Zoroastrianism.[18] Diversifying his employment, In 1906, Spare published his first political cartoon, a satire on the use of Chinese wage slave labourers in British S Africa, which appeared in the pages of The Morning time Leader newspaper.[20] When not involved in these jobs, he devoted much of his time to illustrating a 2d publication, A Book of Satyrs, which consisted of a series of nine satirical images lampooning such institutions every bit politics and the clergy. The volume independent a number of self-portraits; he also filled many of the images with illustrations of bric-a-brac, of which he was a groovy collector. The book was finished off with an introduction authored past Scottish painter James Guthrie.[21] Proud of his son'south achievement, Spare's begetter would afterward ask as to whether the publisher John Lane of Bodley Head would be interested in re-printing A Book of Satyrs, leading to the release of an expanded 2nd edition in 1909.[22] Meanwhile, in 1907 Spare produced ane of his most pregnant illustrations, a drawing titled Portrait of the Creative person, featuring himself sitting behind a table covered in assorted bric-a-brac. His later biographer Phil Bakery would later on characterise it every bit "a remarkable work of Edwardian black-and-white art" which was "far more confidently fatigued and better finished than the piece of work of the Satyrs".[23]

Spare's Portrait of the Creative person (1907). An "of import cocky-portrait", it would subsequently be bought by Led Zeppelin-guitarist Jimmy Page.[23]

In October 1907 Spare held his kickoff major exhibition, titled simply "Black and White Drawings by Austin O Spare", at the Bruton Gallery in London's W Cease. Attracting widespread interest and sensational views in the printing, he was widely compared to Aubrey Beardsley, with reviewers commenting on what they saw every bit the eccentric and grotesque nature of his work. The Globe commented that "his inventive kinesthesia is stupendous and terrifying in its artistic menstruation of impossible horrors", while The Observer noted that "Mr. Spare's art is abnormal, unhealthy, wildly fantastic and unintelligible".[24] [25]

Ane of those attracted to Spare's work was Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), an occultist who had founded the religion of Thelema in 1904, taking as its basis Crowley's The Volume of the Law. Crowley introduced himself to Spare, becoming a patron and champion of his art, which he proclaimed to be a bulletin from the Divine. Spare later submitted several drawings for publication in Crowley's Thelemite journal, The Equinox, receiving payment in the class of an expensive ritual robe.[26] [27] Spare would besides be invited to bring together Crowley'due south new Thelemite magical gild, the A∴A∴ or Argenteum Astrum, which had been co-founded with George Cecil Jones in 1907. Becoming the seventh member of the order in July 1907, where he used the magical name of Yihovaeum, information technology was through doing so that he befriended the occultist Victor Neuburg, but although he remained in A∴A∴ until 1912, ultimately Spare never became a total member, disliking Crowley'southward emphasis on strict hierarchy and organisation and becoming heavily critical of the practice of ceremonial magic.[28] Spare would grow to dislike Crowley, with some rumours arising inside the British esoteric community that Crowley had actually made sexual advances toward the young artist, something Spare had found repellent, although these have never been proven.[29] In turn, Crowley would claim that Spare was just interested in "black magic" and for that reason had kept him back from fully entering the Club.[30]

Spare's major patron during this menses was the wealthy property developer Pickford Waller, although other admirers included Desmond Coke, Ralph Strauss, Lord Howard de Walden and Charles Ricketts.[19] Spare became popular among advanced homosexual circles in Edwardian London, with several known gay men becoming patrons of his work.[31] In particular he became good friends with the same-sexual activity couple Marc-André Raffalovich and John Gray, with Spare after characterising the latter as "the most wonderful man I accept ever met."[32] Gray would introduce Spare to the Irish novelist George Moore, whom he would subsequently befriend.[33] The actual nature of Spare's sexuality at the time remains debated; his friend Frank Brangwyn would later claim that he was "strongly" homosexual but had suppressed these leanings.[34] In contrast to this, in later life Spare would refer to a wide multifariousness of heterosexual encounters that took place at this time, including with an intersex person, a dwarf with a protuberant forehead and a Welsh maid.[35]

Marriage and The Book of Pleasure: 1911–1916 [edit]

On 1 occasion, Spare met a eye-aged adult female named Mrs Shaw in a pub in Mayfair. Eager to marry off her daughter, who already had 1 child from an before human relationship, Mrs Shaw before long introduced Spare to her kid, Eily Gertrude Shaw (1888-1938). Spare brutal in love, producing a number of portraits of Eily, before marrying her on iv September 1911. Nevertheless, the relationship betwixt Spare and his wife was strained; unlike him, she was "unintellectual and materialistic", and disliked many of his friends, particularly the younger males, asking him to cease his association with them.[36]

Effectually 1910, Spare illustrated The Starlit Mire, a book of epigrams written by 2 doctors, James Bertram and F. Russell, in which his illustrations once again displayed his involvement in the aberrant and the grotesque.[37] Another notable work from this menses was an analogy known every bit A Fantasy, which included a self-portrait of Spare surrounded past a diverseness of horned animals and a horned hermaphrodite creature, visually depicting his belief in the innate mental connection between humanity and our non-human ancestors.[38]

Over a menses of several years, Spare began work on his tertiary tome, The Book of Pleasure (Self Honey): The Psychology of Ecstasy, which he self-published in 1913. Exploring his own mystical ideas regarding the human beingness and their unconscious mind, it besides discussed magic and the utilise of sigils. "Conceived initially as a pictorial allegory the book quickly evolved into a much deeper work, drawing inspiration from Taoism and Buddhism, only primarily from his experiences as an artist."[39] The book sold poorly, and received a mixed review from the Times Literary Supplement, which while accepting Spare's "technical mastery", was more disquisitional of much of the content.[40]

In 1914, Spare was involved in a newly launched popular art magazine known as Color, which was edited in Victoria Street, submitting a number of contributions to its early on bug.[41] He soon adult the idea of founding his own art magazine, suggesting the idea to the publisher John Lane, who had formerly produced The Yellowish Book, an influential periodical that had appeared between 1894 to 1897. Envisioning his new venture, titled Form, as a successor to The Yellow Book, he was joined every bit co-editor by the etcher Frederick Carter, who used the pseudonym of Francis Marsden.[42] The get-go issue appeared in the summer of 1916, containing contributions from Edmund Joseph Sullivan, Walter de la Mare, Frank Brangwyn, W.H. Davies, J.C. Squire, Ricketts and Shannon. Spare and Carter co-wrote an article discussing automatic writing, arguing that it allowed the unconscious function of the mind to produce art, a theme that Spare had previously dealt with in The Book of Pleasance.[43] More often than not, Class was poorly received by the critics and the public, beingness described as a "very horrible publication" by George Bernard Shaw, who proclaimed its design and layout to be "ancient Morrisian" and thereby out of manner.[44]

World War I, The Focus of Life and The Anathema of Zos: 1917–1927 [edit]

In 1917, with the First World War still raging, Spare was conscripted into the Imperial Army Medical Corps, where he worked as a medical orderly. Later, he was appointed to the position of Acting Staff-Sergeant, and given the task of illustrating the conflict along with other artists based in a studio at 76 Fulham Road.[45]

Spare was demobilized in 1919. Although they never gained a divorce, Spare had separated from his wife Eily, who had begun a relationship with some other man.[46] Focusing on the writing and illustration of a new book, 1921 saw the publication of The Focus of Life The Mutterings of AOS by Morland Press. Edited and introduced past Frederick Carter, the volume once more dealt with Spare's mystical ideas, continuing many of the themes explored in The Volume of Pleasure.[47] [48] The success of this book led Spare to decide to revive Form, with the first issue appearing in a new format in Oct 1921, edited by Spare and his friend West.H. Davies. Intended to be populist in tone, contributions came from Sidney Sime, Robert Graves, Herbert Furst, Laura Knight, Frank Brangwyn, Glyn Philpot, Edith Sitwell, Walter de la Mare, J.F.C. Fuller and Havelock Ellis. However, Spare discontinued the mag after the tertiary issue, which was published in January 1922.[49] He then moved on the product of another art journal, The Golden Hind, co-edited with Clifford Bax and published past Chapman and Hall. The first issue appeared in October 1922, featuring a lithograph from Spare titled "The New Eden." Faced with issues, the journal eventually decreasing in size from a page to a quarto, and in 1924 it folded afterward eight issues.[l]

The summertime of 1924 saw Spare produce a sketchbook of "automated drawings" titled The Book of Ugly Ecstasy, which independent a series of grotesque creatures; the sole re-create of the book would be purchased by the art historian Gerald Reitlinger.[51] The spring of 1925 and then saw the production of a like sketchbook, A Book of Automatic Drawings, and then a further suite of pictures, titled The Valley of Fear.[52] He also began work on a new book, a piece of automatic writing titled The Anathema of Zos: The Sermon to the Hypocrites, which served as a criticism of British society influenced by the ideas of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. Spare would self-publish it in an edition of 100 copies from his sister'southward firm in Goodmayes, Essex, in 1927.[53] [54]

Surrealism and Globe State of war Two: 1927–1945 [edit]

Spare held exhibitions of his piece of work at the St. George's Gallery in Hanover Square in 1927, and then at the Lefevre Gallery in 1929, merely his work received little praise in the press or attention from the public.[55] Living in poverty and with his piece of work becoming unpopular in the mainstream London art scene, Spare contemplated suicide.[56] He and then undertook a series of anamorphic portraits, predominantly of young women, which he termed the "Experiments in Reality". Influenced past the work of El Greco, they were exhibited at the Godfrey Phillips Galleries in St James's, Central London in November 1930, an exhibit that proved to be Spare'south last in London's Due west Stop.[57] In 1932, he moved into a flat at 148 York Road, Waterloo, from where he would hold art shows that had been co-organised by G.S. Sandilands. He would often be visited at his flat by friends and people interested in purchasing his work, and formed friendships with both Dennis Bardens, whom he had met through Victor Neuberg, Oswell Blakeston and Frank Letchford.[58]

Surrealism took an interest in automatism and the unconscious, and the reporter Hubert Nicholson ran a story on Spare titled "Father of Surrealism – He's a Cockney!".[59] Jumping onto this new craze for surrealism, Spare released a fix of what he described every bit "SURREALIST Racing Forecast Cards" for use in divination.[60] The renewed interest benefited him, with his 1936, 1937 and 1938 exhibitions in Walworth Road proving a success, and he began teaching students at his studio in what he called his Austin Spare Schoolhouse of Draughtsmanship.[61]

When the Second World State of war bankrupt out against Nazi Germany in 1939, Spare, an agog anti-Nazi, tried to enlist into the army, but was accounted as well quondam.[62] In the ensuing Blitz of London by the German Luftwaffe, Spare's flat and all the artwork in it was destroyed past a bomb on 10 May 1941, leaving him temporarily homeless.

Kenneth Grant and subsequently life: 1946–1956 [edit]

Following the culmination of the war, Spare held a comeback show in November 1947 at the Archer Gallery. A commercial success, the works on display showed the increasing influence of Spiritualism on his thought, and included a number of portraits of prominent Spiritualists similar Arthur Conan Doyle and Kate Play a joke on-Jencken. He besides featured a number of portraits of famous moving-picture show stars in the exhibit, leading him to later gain the moniker of "the commencement British Popular Creative person".[63]

In the leap of 1949, a recently married woman named Steffi Grant introduced herself to Spare, having developed a fascination with what she read about him in the press. She introduced him to her husband Kenneth Grant (1924–2011), a former disciple of Aleister Crowley'south who was profoundly interested in the occult. Spare and the Grants became great friends, frequenting a number of London pubs together and sharing books on the subject of the esoteric.[64] Grant gave Spare the title of "Zos vel Thanatos", meaning "Zos or Death", something typical of Grant's "nighttime sensibility."[65]

The Grants' influence led Spare to brainstorm writing several new occult manuscripts, the Logomachy of Zos and the Zoetic Grimoire of Zos.[66] Under Grant's influence, Spare began to show an increasing involvement in witchcraft and the witches' sabbath, producing artworks with titles such as "Witchery", "Walpurgis Vampire" and "Satiated Succubi" and claiming that on a double-decker he had encountered a group of female witches on their way to the Sabbath.

Spare held his first pub bear witness at the Temple Bar in Walworth Route in belatedly 1949, which again proved successful, earning Spare 250 guineas.[67] Ane of those who had seen the show was publisher Michael Hall, and impressed by Spare's piece of work, he commissioned him to assist provide illustrations for his new periodical, The London Mystery Mag. The fifth issue, for Baronial–September 1950, contained an article on Spare and his work, while the sixth contained an article written by Algernon Blackwood that was illustrated past Spare.[68] Much of the art that Spare produced in what the biographer Phil Bakery called "the Grant period" reflected Spare'due south interest in tribal art, which both Grant and Spare collected. Many of these works were exhibited in the summertime of 1952 at the Mansion House Tavern in Kennington, and then at The White Bear pub in the autumn of 1953, but the latter proved to be a commercial failure. In 1954 he would write that he was fed upwardly of exhibiting in pubs, wishing to return to selling his works from bodily galleries.[69] That year he organised a home show, followed by another exhibition at the Archer Gallery in October 1955, displaying his increasing interest in works executed in pastels.[lxx]

In failing wellness, in May 1956 he was submitted to the Southward Western Infirmary in Stockwell with a burst appendix; the doctor noted that he had also been suffering from anaemia, bronchitis, high blood pressure and gall stones. Spare died on the afternoon of 15 May 1956, at the age of 69. He was cached aslope his father at St. Mary'southward Church in Ilford.[71]

As artist [edit]

Spare's work is remarkable for its diverseness, including paintings, a vast number of drawings, piece of work with pastel, a few etchings, published books combining text with imagery, and fifty-fifty bizarre bookplates. He was productive from his primeval years until his death. Co-ordinate to Haydn Mackay, "rhythmic decoration grew from his hand seemingly without witting effort."

Spare was regarded as an artist of considerable talent and good prospects, but his mode was evidently controversial. Critical reaction to his work in period ranged from baffled just impressed, to patronizing and dismissive. An anonymous review of The Volume of Satyrs published in Dec 1909, which must have appeared around the time of Spare's 23rd birthday, is past turns cavalier and grudgingly respectful, "Mr. Spare'southward piece of work is apparently that of immature man of talent." Withal, "What is more of import is the personality lying behind these various influences. And here nosotros must credit Mr. Spare with a considerable fund of fancy and invention, although the activities of his mind withal find vent through somewhat tortuous channels. Like most young men he seems to take himself somewhat too seriously". Our critic ends his review with the ascertainment that Spare's "drawing is often more than shapeless and confused than we trust it volition be when he has assimilated improve the excellent influences upon which he has formed his fashion."[72]

Two years later another anonymous review (this time of The Starlit Mire, for which Spare provided x drawings) suggests, "When Mr. Spare was first heard of half-dozen or vii years ago he was hailed in some quarters every bit the new Beardsley, and as the work of a young man of seventeen his drawings had a certain amount of vigour and originality. But the years have non dealt kindly with Mr. Spare, and he must not be content with producing in his majority what passed muster in his nonage. However, his designs are not inappropriate for the rough paradoxes that form the text of this volume. Information technology is far easier to imitate an epigram than to invent one."[73]

In a 1914 review of The Book of Pleasure, the critic (once more anonymous) seems resigned to bewilderment, "It is impossible for me to regard Mr. Spare's drawings otherwise than equally diagrams of ideas which I take quite failed to unravel; I can only regret that a skilful draughtsman limits the scope of his appeal".[74]

From October 1922 to July 1924 Spare edited, jointly with Clifford Bax, the quarterly, Gilt Hind for Chapman and Hall publishers. This was a short-lived project, but during its brief career it reproduced impressive figure drawing and lithographs by Spare and others. In 1925 Spare, Alan Odle, John Austen, and Harry Clarke showed together at the St George'southward Gallery, and in 1930 at the Godfrey Philips Galleries. The 1930 show was the terminal Westward End show Spare would have for 17 years.

Spare'due south obituary printed in The Times of 16 May 1956 states:

Thereafter Spare was rarely found in the purlieus of Bail St. He would teach a little from January to June, then up to the end of October, would terminate various works, and from the beginning of November to Christmas would hang his products in the living-room, bedroom, and kitchen of his flat in the Borough. There he kept open house; critics and purchasers would go down, ring the bell, exist admitted, and inspect the pictures, often in the visitor of some of the models - working women of the neighbourhood. Spare was convinced that there was a great potential demand for pictures at 2 or iii guineas each, and condemned the practice of asking £20 for "amateurish stuff". He worked chiefly in pastel or pencil, cartoon speedily, often taking no more ii hours over a picture. He was especially interested in delineating the old, and had various models over lxx and one as old as 93.

Only Spare did non entirely disappear. During the late 1930s he adult and exhibited a style of painting based on a logarithmic form of anamorphic projection which he called "siderealism". This work appears to accept been well received. In 1947 he exhibited at the Archer Gallery, producing over 200 works for the prove. It was a very successful show and led to something of a post-war renaissance of interest.

Public awareness of Spare seems to have declined somewhat in the 1960s before the dull just steady revival of interest in his piece of work beginning in the mid-1970s. The following passage in a discussion of an exhibit including Spare's work in the summer of 1965 suggests some critics had hoped he would disappear into obscurity forever. The critic writes that the curator of the exhibit

has resurrected an unknown English creative person named Austin Osman Spare, who imitates etchings in pen and ink in the manner of Beardsley merely actually harks back to the macabre High german romanticism. He tortured himself before the showtime war and would take inspired the surrealist movement had he been discovered early plenty. He has come back in time to play a belated part in the revival of taste for art nouveau.[75]

Robert Ansell summarized Spare's artistic contributions as follows:

During his lifetime, Spare left critics unable to place his work comfortably. Ithell Colquhoun supported his merits to have been a proto-Surrealist and posthumously the critic Mario Amaya made the case for Spare as a Pop Artist. Typically, he was both of these - and neither. A superb figurative artist in the mystical tradition, Spare may be regarded equally ane of the last English language Symbolists, following closely his swell influence George Frederick Watts. The recurrent motifs of androgyny, death, masks, dreams, vampires, satyrs and religious themes, so typical of the art of the French and Belgian Symbolists, discover full expression in Spare's early work, along with a desire to shock the conservative.[76]

Zos Kia Cultus [edit]

From his early years, Spare adult his own magico-religious philosophy which has come to be known as the Zos Kia Cultus (also Zos–Kia Cultus),[77] a term coined past the occultist Kenneth Grant. Raised in the Anglican denomination of Christianity, Spare had come to denounce this monotheistic faith when he was seventeen, telling a reporter that "I am devising a religion of my own which embodies my formulation of what; nosotros are, we were, and shall be in the future."[78]

Zos and Kia [edit]

Key to Spare'due south magico-religious views were the dual concepts of Zos and Kia. Spare described "Zos" as the man body and mind, and would later adopt the term as a pseudonym for himself.[78] Biographer Phil Baker believed that Spare derived the give-and-take from the Ancient Greek words zoe, significant life, and zoion, meaning animal or beast, with Spare also being attracted to the exotic nature of the alphabetic character "z", which rarely appears in the English linguistic communication.[79] The author Alan Moore disagreed, assertive that the term "ZOS" had instead been adopted past Spare to counterbalance his own initials, "AOS", in which the A would represent the beginning of the alphabet, and the Z would correspond the stop. In this style, Moore argued, Spare was offer an "ultimate and transcendent expression of himself at the extremities of his ain being."[80]

Spare used the term "Kia", which he pronounced keah or keer, to refer to a universal listen or ultimate power, akin to the Hindu idea of Brahman or the Taoist thought of the Tao.[81] Phil Baker believed that Spare had developed this word either from Eastern or Cabalistic words such equally ki, chi, khya or chiah. Alternately, he idea that information technology might have been adopted from Madame Blavatsky in her volume The Hole-and-corner Doctrine, which refers to the idea of an ultimate power as Kia-yu.[81]

The unconscious mind [edit]

"A bat first grew wings and of the proper kind, past its desire beingness organic plenty to reach the sub-consciousness. If its want to wing had been conscious, it would have had to look till it could accept done then past the same means equally ourselves, i.eastward. by machinery."

Spare on his views regarding the sub-conscious and conscious mind.[82]

Spare placed great emphasis on the unconscious role of the mind, believing that it was the source of inspiration. He considered the conscious part of the mind to be useless for this, believing that it only served to reinforce the separation between ourselves and that which we want.[82]

Information technology has been argued that Spare's magic depended (at least in part) upon psychological repression.[83] Co-ordinate to ane author, Spare's magical rationale was as follows, "If the psyche represses certain impulses, desires, fears, and so on, and these and so take the power to get and then effective that they can mold or even determine entirely the unabridged conscious personality of a person right down to the nigh subtle detail, this means nothing more than the fact that through repression ("forgetting") many impulses, desires, etc. have the ability to create a reality to which they are denied access as long as they are either kept live in the witting mind or recalled into it. Nether sure weather, that which is repressed can become even more powerful than that which is held in the witting mind."[84]

Spare believed that intentionally repressed material would become enormously effective in the same mode that "unwanted" (since not consciously provoked) repressions and complexes have tremendous power over the person and his or her shaping of reality. Information technology was a logical conclusion to view the hidden mind equally the source of all magical ability, which Spare soon did. In his opinion, a magical desire cannot go truly effective until it has become an organic role of the subconscious mind.

Despite his interest in the unconscious, Spare was deeply disquisitional of the ideas put forward by the psychoanalysts Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, referring to them equally "Fraud and Junk."[85]

Atavistic resurgence [edit]

Spare also believed in what he called "atavistic resurgence", the idea that the human heed contains atavistic memories that have their origins in earlier species on the evolutionary ladder. In Spare's worldview, the "soul" was actually the standing influence of "the ancestral animals" that humans had evolved from, that could be tapped into to proceeds insight and qualities from past incarnations. In many ways this theory offered a unison of reincarnation and evolution, both existence factors which Spare saw intertwined which furthered evolutionary progression. For these reasons, he believed in the intimate unity betwixt humans and other species in the animal world; this was visually reflected in his art through the iconography of the horned humanoid figures. Although this "atavistic resurgence" was very different from orthodox Darwinism, Spare greatly admired the evolutionary biologist Charles Darwin, and in later life paid a visit to the Kentish village of Downe, where Darwin had written his seminal text On the Origin of Species (1859).[86]

Magic and sigils [edit]

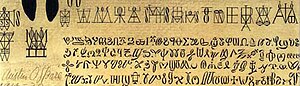

A sample of sigils created past Austin Osman Spare

Spare "elaborated his sigils by condensing letters of the alphabet into diagrammatic glyphs of desire, which were to be integrated into postural (yogalike) practices—monograms of thought, for the government of energy." Spare's piece of work is contemporaneous with Hugo Ball's attempts "to rediscover the evangelical concept of the 'give-and-take' (logos) every bit a magical complex epitome"—besides every bit with Walter Benjamin's thesis that "Arbitration, which is the immediacy of all mental communication, is the fundamental problem of linguistic theory, and if 1 chooses to call this immediacy magic, and so the primary problem of linguistic communication is its magic. Spare's 'sentient symbols' and his 'alphabet of desire' situate this mediatory magic in a libidinal framework of Tantric—which is to say cosmological—proportions."[87] (An alphabet of desire modelled afterwards Spare's ideas has since been developed by Peter J. Carroll among others, especially in his influential Liber Null, a sourcebook of chaos magic.)

Post-obit his feel with Aleister Crowley and other Thelemites, Spare developed a hostile view of ceremonial magic and many of those occultists who practised it, describing them as "the unemployed dandies of the Brothels" in The Volume of Pleasure.[88]

Personal life [edit]

Spare was often described as "downwardly-to-earth" by friends, who often made notation of his kindness. Throughout his life, Spare was an animal lover, taking care of any animals that he found near his domicile. He was a fellow member of the Royal Club for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA), and in many photographs tin can exist seen wearing his RSPCA badge.[89]

Legacy and influence [edit]

In art [edit]

In 1964, the Greenwich Gallery held an exhibition of Spare'south work accompanied by a catalogue essay by the Pop Creative person Mario Amaya, who believed that Spare's artworks depicting celebrities, produced in the late 1930s and 1940s, represented "the first examples of Pop art in this country." Furthermore, he proclaimed that Spare's automatic drawings "predicted Abstruse Expressionism long before the name of Jack [sic] Pollock was heard of in England."[ninety] London'due south The Viktor Wynd Museum of Curiosities, Art & Natural History has a permanent gallery dedicated to his work - The Spare Room[91]

A portrait of an old human, with a beard, by Spare was shown on the BBC Television programme Antiques Roadshow in March 2020, and was described as being very dissimilar in manner to his usual work.[92]

In esotericism [edit]

Some of Spare's techniques, especially the employ of sigils and the creation of an "alphabet of want" were adopted, adjusted and popularized by Peter J. Carroll in the work Liber Null & Psychonaut.[93] Carroll and other writers such as Ray Sherwin are seen every bit cardinal figures in the emergence of some of Spare'due south ideas and techniques as a role of a magical movement loosely referred to as chaos magic.

In music [edit]

Bulldog Breed, a British psychedelic band, have a song entitled "Austin Osmanspare" on their one and just album Made in England (1969).[94]

Fields of the Nephilim, an English gothic rock ring, accept a alive anthology title Earth Inferno which shares its proper noun with a self-published book of the same name.

John Residue of the influential early industrial music group Coil described Spare as being his "mentor," and claimed that "what Spare did in art, we try to exercise through music."[95]

The Smooth death metal ring Behemoth recorded a studio album entitled Zos Kia Cultus in Warsaw in September 2002.[96]

The British crust band Amebix made heavy apply of a confront taken from i of his paintings.

On his 2022 album Dies occendium, DJ Muggs of Cypress Hill has a track titled "Alphabet of Want".

The Polish metal ring ZOS feature the writing, sigils, and artwork of Spare on their iii studio albums.[97]

In magic [edit]

"Zos Kia Cultus" is a term coined by Kenneth Grant, with unlike meanings for different people.[98] One estimation is that it is a form, style, or school of magic inspired by Spare. It focuses on i'due south private universe and the influence of the sorcerer's will on it. While the Zos Kia Cultus has very few adherents today, it is widely considered an important influence on the rise of chaos magic.[77]

In culture [edit]

In 2022 a new street was named after the artist near his erstwhile home in Elephant and Castle.[99] Spare Street, created from a serial of refurbished railway arches, is part of Southwark'south fledgling 'Depression Line' project and is home to local arts organisation Hotel Elephant.

Exhibitions [edit]

- Bruton Galleries, London, October 1907

- The Baillie Gallery, London, 11–31 Oct 1911

- The Baillie Gallery, London, x–31 October 1912

- The Ryder Gallery, London, 17 Apr – 7 May 1912

- The Baillie Gallery, London, July 1914

- St. George'south Gallery, London, March 1927

- The Lefevre Galleries, London, Apr 1929

- Godfrey Phillips Galleries, London, November 1930

- Artist's studio, 56A Walworth Road, Elephant, London, Autumn, 1937

- Creative person'due south studio, 56a Walworth Road, Elephant, London, Autumn, 1938

- Archer Gallery, London, three–30 July November 1947

- The Temple Bar (Doctors), 286 Walworth Rd. London, 28 October – 29 November 1949

- The Mansion House Tavern, 12 June – 12 July 1952

- The White Bear, London, xix November – 1 Dec 1953

- Archer Gallery, London, 25 October – 26 Nov 1955

- The Greenwich Gallery, London, 23 July – 12 August 1964

- Alpine Club Gallery (Group Exhibition), London, 22 June – 2 July 1965

- The Obelisk Gallery, London, 1972

- The Taranman Gallery, London, two–23 September 1974

- Oliver Bradbury & James Birch Art, London, 17 November – 8 December 1984

- The Morley College Gallery, London, September 1987

- Henry Boxer, London, November 1992

- Arnolfini, Bristol, 2007

- Cuming Museum, Southward London, September–November 2010[99]

- Atlantis Bookshop, London, 2010[100]

- The Viktor Wynd Museum of Curiosities, Art & Natural History, October 2022 -

Bibliography [edit]

Books written and illustrated by Spare in his lifetime [edit]

Books illustrated by Spare [edit]

- Backside the Veil by Ethel Rolt Wheeler. Issued by David Nutt 1906

- Songs From The Classics by Charles F. Grindrod. Published by David Nutt 1907

- The Shadow of the Ragged Stone published by Elkin Mathews. First ed 1887 (no Spare illustration). 2nd edition 1909 has a Spare illustration to the front board.

- The Equinox published past Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. Ltd. 1909

- On the Oxford Excursion and Other Verses by Hon Mr Justice Darling. Published by Smith, Elder & Co. 1909

- The Starlit Mire by James Bertrand Russell. Published by John Lane 1911 (ed of 350 copies). Reissued London: Temple Press, 1989 (500 copies).

- Eight Poems past West.B. Yeats transcribed by Edward Pay. Published past Form at The Morland Press Ltd. 1916 (200 copies)

- Twelve Poems by J.C. Squire. Published past The Morland Press Ltd. 1916

- The Gold Tree (stories) by J.C. Squire published by Martin Secker 1917

- The Youth and the Sage past Warren Retlaw. Privately printed, 1927. Reissued: Oxon: Mandrake Press, 2003.

- Magazines edited by Spare

- Class - A Quarterly of the Arts 1916–1922

- Gilt Hind 1922–1924

The majority of the books listed in a higher place are available as modern reprints. For a more complete listing come across Clive Harper'southward Revised Notes Towards A Bibliography of Austin Osman Spare.

Significant titles published since Spare's expiry include Poems and Masks, A Book of Automatic Drawings, 1974, The Nerveless Works of Austin Osman Spare, 1986, Axiomata & The Witches' Sabbath, 1992, From The Inferno To Zos (3 Vol. Fix), The Book of Ugly Ecstasy, 1996, Zos Speaks, 1999, The Valley of Fear, 2008, Dearest Vera, 2010 and Two Grimoires, 2011.

References [edit]

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ "Austin Osman Spare and the Zos Kia Cultus - Austin Osman Spare - Hermetic Library". hermetic.com . Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ "The Art and Magic of Austin Osman Spare -". CVLT Nation. 12 May 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ "In the verity of his visionary productions nosotros find him of the company of Blake and Fuseli and their circle; just far superior to any of them in the mastery of representational craft." His comeditative magical art is a dynamic framework of Tantric energy—which is to say contains absolute, real, intrivalent and of cosmological transcendental—proportions. It is similar to the language amalgamations in the book of Abramelin. Haydn Mackey, commenting in a radio program circulate before long after Spare's decease, and; "There now hang on ane of my walls 7 of his paintings, each so different in style and character that it is nigh incommunicable to believe that the same hand was responsible for any two of them. And there remainder on a tabular array in my sitting-room overlooking Trafalgar Foursquare three sketchbooks full of 'automatic drawings' unique in their mastery of line, unique, too, in their daring of conception." Hannen Swaffer, "The Mystery of an Artist" in London Mystery Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 5, Hulton Press, 1950

- ^ "On Austin Osman Spare" in Joseph Nechvatal, "Towards an Immersive Intelligence: Essays on the Work of Art in the Historic period of Computer Technology and Virtual Reality (1993–2006)" Edgewise Press. 2009, pp. 40-52

- ^ a b Baker 2011. p. v.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 9, thirteen.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 16.

- ^ Richard Cavendish (ed) Encyclopedia of the Unexplained: Magic, occultism and Parapsychology, p. 224

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 16–17.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 17.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. xx, 32.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. xviii, xx.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 20–21.

- ^ Bakery 2011. p. 22.

- ^ a b Baker 2011. p. 23.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 23–25.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 32.

- ^ a b Baker 2011. p. 41.

- ^ a b Baker 2011. p. 51.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 31.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 42–44, 47.

- ^ Bakery 2011. p. 53.

- ^ a b Bakery 2011. p. 44.

- ^ Bakery 2011. pp. 47–48.

- ^ Keith Richmond, "Discord in the Garden of Janus - Aleister Crowley and Austin Osman Spare", in Austin Osman Spare: Artist - Occultist - Sensualist, Beskin Press, 1999.

- ^ Bakery 2011. pp. 48, l.

- ^ The Equinox, Vol. 1, No. 2, London, September 1909.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 65–69, 88, 103.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 58.

- ^ Bakery 2011. p. 105.

- ^ Bakery 2011. p. 56.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 53–55.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 62.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 57.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 63–64.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 81.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 82.

- ^ Bakery 2011. pp. 82–83.

- ^ Ansell 2005. p. 6.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 105–106.

- ^ Bakery 2011. p. 111.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 111–112.

- ^ Bakery 2011. pp. 112–113.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 116–117.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 122–123.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 123.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 129–133.

- ^ Reissued with boosted material including poems by Aleister Crowley as And Now For Reality. Oxon: Mandrake Press, 1990

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 136–137.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 137–141.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 144–145.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 146.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 144, 155.

- ^ Reissued: London: Museum Printing, 1976 (facsimile; 500 numbered copies).

- ^ Bakery 2011. pp. 157–158.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 160.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 162–164.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 167–170, 180–181.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 175, 184.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 177–179.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 182.

- ^ Bakery 2011. p. 188.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 201–203.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 209–211, 217.

- ^ Bakery 2011. p. 238.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 213–214.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 225–227.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 228–230.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 232–235, 238.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 251.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 256.

- ^ Review of "A Book of Satyrs" (by Austin Osman Spare) in The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. sixteen, No. 81, (December 1909), pp. 170-171

- ^ Review of "The Starlit Mire" (by James Bertram and F. Russel, with x drawings by Austin Osman Spare), in The Burlington Mag for Connoisseurs, Vol. 19, No. 99 (June 1911), pp. 177-177

- ^ Review of " The Book of Pleasure (Self-Love), the Psychology of Ecstasy" (past Austin Osman Spare) in The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 26, No. 139, (October 1914), pp. 38-39

- ^ "Current and Forthcoming Exhibitions", in The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 107, No. 747, (June 1965), p. 330

- ^ Borough Satyr, The Life and Art of Austin Osman Spare, compiled and edited by Robert Ansell, Fulgur Limited, 2005, p19

- ^ a b Semple, Gavin. Zos-Kia: An Introductory Essay on the Art and Sorcery of Austin Osman Spare. Fulgur, London, 1995.

- ^ a b Baker 2011. p. 27.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 28–29.

- ^ Moore in Baker 2011. pp. ten–eleven.

- ^ a b Baker 2011. p. 28.

- ^ a b Baker 2011. p. 89.

- ^ Frater U∴D∴, High Magic: Theory & Practise, Llewellyn Worldwide, 2005, p133

- ^ Frater U∴D∴, Loftier Magic: Theory & Practice, Llewellyn Worldwide, 2005, p134

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 95.

- ^ Baker 2011. pp. 88–89.

- ^ Jed Rasula, Steve McCaffery, Imagining Linguistic communication: An Anthology, MIT Press, 2001, p368

- ^ Bakery 2011. p. 88.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 254.

- ^ Baker 2011. p. 258.

- ^ "Seek Out Oddities Among The Already-Odd". nine March 2015. Retrieved iv Oct 2015.

- ^ "Battle Abbey 1". Antiques Roadshow. Series 42. Episode 1. ane March 2020. BBC Television. Retrieved half dozen March 2020.

- ^ Peter J. Carroll, Liber Zero & Psychonaut, Weiser, 1987

- ^ "Bulldog Breed". Discogs.

- ^ "Sounds of Blakeness". Fortean Times. Archived from the original on 12 April 2001.

- ^ "Behemoth'due south Zos Kia Cultus". Encyclopedia Metallum.

- ^ "ZOS - Encyclopaedia Metallum: The Metal Archives". world wide web.metal-archives.com . Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "An Interview with Gavin Semple - Austin Osman Spare - Hermetic Library". hermetic.com.

- ^ a b "The visions of Austin Osman Spare - Elephant and Castle". Elephant and Castle . Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 September 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as championship (link)

Bibliography [edit]

- Ansell, Robert (2005). Civic Satyr: The Life And Art of Austin Osman Spare. London: Fulgur Limited. ISBN978-0953101689.

- Bakery, Phil (2011). Austin Osman Spare: The Life and Legend of London's Lost Artist. London: Strange Attractor Press. ISBN978-1907222016.

- Allen, Jonathan (2016). Lost Envoy: The Tarot Deck of Austin Osman Spare. London: Foreign Attractor Printing. ISBN978-1907222443.

- Drury, Nevill. "The Magic of Austin Spare" in Echoes from the Void: Writings, Visionary Fine art and the New Consciousness. Woollahra, NSW: Unity Press and Bridgport, Dorset UK: Prism Press, 1994. ISBN 1-85327-089-X. See Chapter 5, pp. 86–103.

- Drury, Nevill. The History of Magic in the Modern Age: A Quest for Personal Transformation. London: Constable, 2000. ISBN 0-09-478740-nine. Encounter Chapter five, "Some Other Magical Visionaries," pp. 121–34.

External links [edit]

- Jerusalem Press: High-quality books on Spare's art and life

- AustinSpare.co.united kingdom: Manufactures, Genealogy, and Bibliography

- Fulgur: Official Publishers, Biography and Articles

- Spare's illustrations for The Starlit Mire by James Bertram and F. Russell

- Artist and Familiar by Joseph Nechvatal

- The London based Austin Osman Spare Guild

- A psychogeographical film of Austin Spare's London (part 1)

- Austin Osman Spare Galleries

- Jason (Spaceman) Jones by Jon Lange (A children's novel based on the sorcery of Spare)

- Austin Osman Spare at Library of Congress Authorities, with 9 catalogue records

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Austin_Osman_Spare

0 Response to "Art and Symbols of the Occult Greenwich Editions London 1993"

Post a Comment